This article was written for The DC Line and you can read it on that site here.

Sitting in the rotunda of the Corcoran School of the Arts & Design’s renovated Flagg Building across from the White House hours before the highly anticipated opening of artist Robin Bell’s exhibition Open, Corcoran director and curator Sanjit Sethi reflected on the show’s inspiration. “I think it’s important for us to have dialogues about what happens when cultural institutions get something wrong,” he said.

Sethi was commenting both on Bell’s artworks in Open, which reflect on themes of transparency and dialogue, and the stimulus for the exhibit: a troubling episode of censorship at the Corcoran back in 1989, long before its transformation from an independent institution to a school within The George Washington University.

Unusually for a fine art exhibition, Open is described as a “prelude” to another show. The upcoming 6.13.89, curated by Sethi, will encourage investigation of the Corcoran’s fateful decision on June 13, 1989, to cancel its planned display of The Perfect Moment, a traveling exhibition of Robert Mapplethorpe’s photographs. The Perfect Moment’s first stops — in Philadelphia and then Chicago — spurred growing protest from people who decried the exhibition as an example of government funding for artwork they deemed immoral. The show included gay-themed works that socially conservative politicians and “family values” advocacy groups lambasted as pornography masquerading as art.

Open is Bell’s first solo museum show, and it includes more than the political text-based artwork the artist is best known for. With its scrolling text and blinking lights, the exhibition is engaging and self-aware — like a massive resistance group selfie. Bell’s works float in and balance through the various atrium and first-floor gallery spaces. In one section of the atrium, lights that blink and change colors hang on either side of a black video screen with white text that reads, “It is happening here.” The statement might be interpreted as the artist’s opinion about the Corcoran, and the District, or as an ironic reference to the canceled 1989 exhibition that did not happen.

Bell’s art works, several of which have gone viral since President Donald Trump’s election, are equal parts humor and anger. His best-known works are guerilla outdoor projections of text, which he and others capture in short videos distributed on social media. One of his early viral works projected the words “INSERT EMOLUMENTS HERE” on the side of the Trump International Hotel on Pennsylvania Avenue NW, with a large arrow under the words pointing at the doorway into the hotel.

While Bell’s well-known guerrilla displays are sometimes 50 feet tall, conceptually the work is compact. The artworks in Open reveal more of Bell’s technical range, as well as a more complex and allegorical relationship to his subject matter.

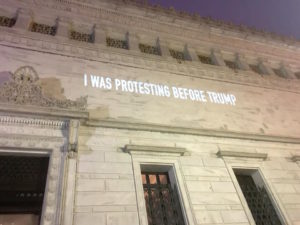

Bell’s works don’t usually articulate the artist’s own voice, but one projection on the outside of the Flagg Building during the opening — “I Was Protesting Before Trump” — playfully did just that. The exhibition also features a video that rolls like fog across the atrium steps, a projection of overlapping 10-foot faces, and scrolling phrases that hang across and beneath the upper balustrade in the foyer. There’s something familiarly peripatetic and temporary about Bell’s work, even in this museum space, where the art’s existence doesn’t cause threat of imminent arrest (as one of his unlicensed public artworks did last week, resulting in a misdemeanor citation from U.S. Capitol Police for one of Bell’s projectionists).

Sethi said Bell’s exhibit is the museum’s latest effort to dedicate its atrium to “exhibition projects that involve critical social dialogues … that we think need to be part of a broader context.”

When asked if he condemned the Corcoran’s 1989 decision to cancel, Sethi explained, “I’m less engaged in the forensic examination of who did what and what the cause was. The question for me is the fidelity of the Corcoran Gallery to the commitment they had made to show this work… The question for me is about how do cultural institutions handle controversy?”

In an interview prior to the opening, Bell was less equivocal. He called the 1989 cancellation “a disservice not just to the institution, but to the entire arts community.” In interview with the university prior to the opening Bell said his Open is about asking the audience to reflect on closure, and cancellation. “As thinkers, as people and as educators we want to talk about openness,” Bell said.

Open — on display through March 31 — and the upcoming 6.13.89 — the dates for which have not been announced — reflect on a darker part of the Corcoran’s history. “It’s important to go ahead and exhume one of the greatest ghosts of the Corcoran’s past,” Sethi said.

Looking back to summer 1989

In the summer of 1989 the District was the center of what came to be called “the Culture Wars,” a series of impassioned, high-profile debates about arts funding, morality, censorship, and homosexuality.

Curated by Janet Kardon and developed under the auspices of the Institute of Contemporary Arts in Philadelphia, The Perfect Moment was scheduled for display in five cities after its winter 1988 debut in Philadelphia. Conservative groups including the American Family Association began to protest the exhibition soon after its opening, saying the exhibition included “indecent” images. The Perfect Moment exhibition was developed in part through grant funding from the National Endowment for the Arts, and the exhibition’s scheduled arrival in DC coincided with some Republican members of Congress urging elimination of all arts funding after seeing federal dollars go to some projects out of step with their values.

The Corcoran Gallery of Art’s decision to cancel its display of A Perfect Moment just weeks before the planned opening led to intense public scrutiny and prompted mentions in scores of newspaper articles, editorials and opinion pieces that have been preserved in the Corcoran’s archive.

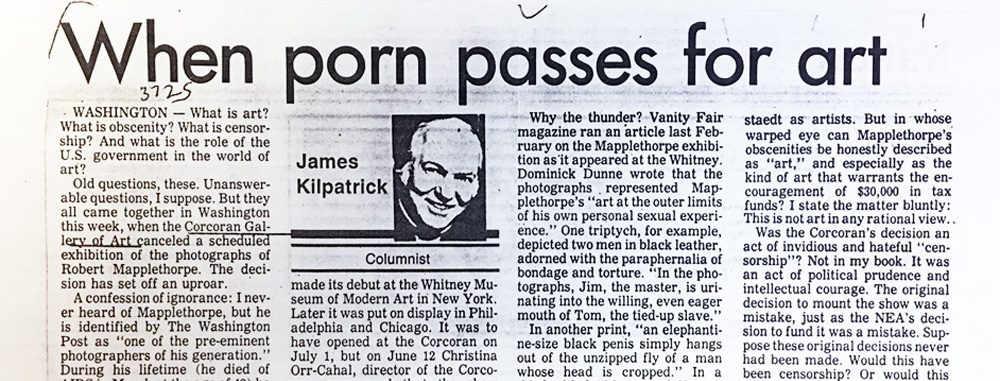

It’s nearly unimaginable that any museum decision today would make headlines over an entire summer as the Corcoran decision did, but national interest was fomented in widely read political opinion pieces. One column by conservative commentator Patrick Buchanan — who backed the cancellation and said the show never should have received any government funding — was published in more than 30 newspapers in the U.S. and Europe between June 16 and June 25. The various headlines included “Obscenity at the Taxpayer’s Expense” (The News & Observer, Raleigh, N.C., June 16), “A Mere Label Can’t Turn Pornography Into Art” (The Florida Times-Union, Jacksonville, Fla., June 20), and “No Censorship Involved Here” (Taunton Daily Gazette, Taunton, Miss., June 20).

Two major newspaper editorial boards weighed in subsequently, criticizing the Corcoran’s decision-makers. The New York Times published an editorial headlined “Caving in at the Corcoran” on June 23, 1989. “The Corcoran unwisely chose to repudiate its own artistic judgment. Instead of helping to avoid controversy, the gallery’s cave-in only attracted it,” the newspaper wrote.

The Washington Post’s editorial board agreed days later: “They scheduled the show without adequate understanding of what was in it … and then, at the first sign of trouble on Capitol Hill, panicked and canceled with much hand-wringing about not wanting to get into politics or to give government an excuse for cutting funds.”

After the Corcoran’s cancellation, The Perfect Moment was shown in the District by last-minute arrangement at the Washington Project for the Arts, and the tour proceeded to other cities amid continued controversy.

A full understanding of the Corcoran’s decision requires a value judgment on whether the cancellation in fact amounted to censorship of Mapplethorpe’s artwork based on its homosexual imagery.

Mapplethorpe had died three months earlier of complications from AIDS. Reacting to the cancellation, Urvashi Vaid, a spokesperson for the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, told the Washington Blade at the time, “It is appalling that [Sen.] Jesse Helms succeeded in having a pre-emptive impact on homoerotic art.”

But objections to the exhibition were more complex than simply objecting to any depiction of homosexuality.

The Perfect Moment was a comprehensive retrospective of the artist’s work, including 125 images. While the majority of the images were from Mapplethorpe’s more commercial work — including pictures of celebrities and flowers — the exhibition also included depictions of naked children and homosexual sadomasochism. One well-known image shows the photographer’s buttocks in profile, a bullwhip protruding like a horse’s tail. Another displays a young girl seated on the floor, her white dress pulled up to her knees exposing her naked groin as she looks innocently into the camera.

Even though the photographer had parental permission, several of the images from this series are no longer exhibited as art in adherence to 21st-century standards of child protection. Critics of the exhibition, and federal funding of the show, charged that Mapplethorpe’s images were criminal, not art. A June 22, 1989, commentary by The Miami Herald’s editorial board referenced Mapplethorpe’s work to bolster objections to government funding of artist Andres Serrano’s artwork “Piss Christ”: “Also disturbing is the traveling exhibit of photographs by Robert Mapplethorpe that include explicit sadomasochism and child nudes.”

Uproar over the Corcoran’s decision to cancel the exhibit required a villain — a censor. That person was identified as the museum’s executive director — Christina Orr-Cahall, who resigned later that year — even though it was the Board of Trustees that canceled the show. When consultants performed a subsequent audit of the Corcoran’s decision-making process, they attributed the unanimous decision to the board being too large to keep its members well-informed. In response to the audit’s recommendation, the Corcoran reduced the size of its board by two-thirds. The presence of fewer board members — along with dwindling commitments from outsiders soured by the controversy — had a predictable impact on the institution’s coffers, and it’s not a stretch to argue the Corcoran’s demise as an independent institution can be traced to the summer of 1989.

Ironically, given the hatred poured on her as a “censor,” Orr-Cahall’s action may have saved the National Endowment for the Arts as we know it today. By proposing to the board members that they not display the controversial photographs in DC while Congress was debating restrictions on or outright elimination of federal arts funding, she created a major new issue in the debate. On the day the Corcoran announced the cancellation, then-U.S. Rep. Dick Armey, R-Texas, called images by Mapplethorpe “morally repugnant trash” and Hugh Southern, the acting head of the NEA, told Congress that he would “try and weed out” objectionable artwork. The cancellation decision prompted such a strong backlash against censorship, and in support of free expression, that federal arts funding continued.

The relevance of Robin Bell

Now, 30 years later, the works of another artist some see as courting controversy occupy the Corcoran, communicating a related message. Bell’s art, including his work in Open, encourages transparency and holding power to account.

The history of Washington, DC, is alive in the memories of longtime residents, and the legacies of hometown artists like Langston Hughes, Duke Ellington and Alma Thomas exist like small bonfires around which residents warm. But other memories live on as deep scars, occasionally causing a collective hiccup, and the cancellation of the Robert Mapplethorpe show at the Corcoran the summer of 1989 is one of those.

A few months ago, when the DC Commission on the Arts and Humanities pushed a new contract out to grantees attempting to restrict funding for political or offensive works, The Washington Post reported “the short-lived controversy sent shock waves through the city’s arts community and had many recalling the 1980s culture wars.” And for one summer, the summer of 1989, the Corcoran Gallery of Art served as a battleground in those culture wars.

The new exhibit, according to Sethi, reopens a dialogue set to continue with 6.13.89, which has not been announced in detail but which will include documents from the Corcoran’s archive.

“This institution has an opportunity to talk about its values,” Sethi said, “and to talk about ways that we can talk about critique. Critique of systems. Critique of individuals. Critique of policy. And to do so in provocative manners. And that’s what you start to see here.”

Robin Bell was sanguine about what Open might mean for him personally. “The biggest difference,” he said, “is that people will be able to see [my artwork], to come over the next two months and see it as opposed to seeing it online and appreciating it that way.”

In Open we find Robin Bell and the Corcoran looking back on what went wrong and are encouraged to look back with them.

The exhibition continues through March 31, with public access from 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. Tuesday through Friday and from 1 to 6 p.m. Saturday and Sunday at the Flagg Building, 500 17th St. NW.