Career trajectory for African-American expressionist led from DC Public Schools to the Whitney Museum

This article was written for The DC Line. You can read it on their website here.

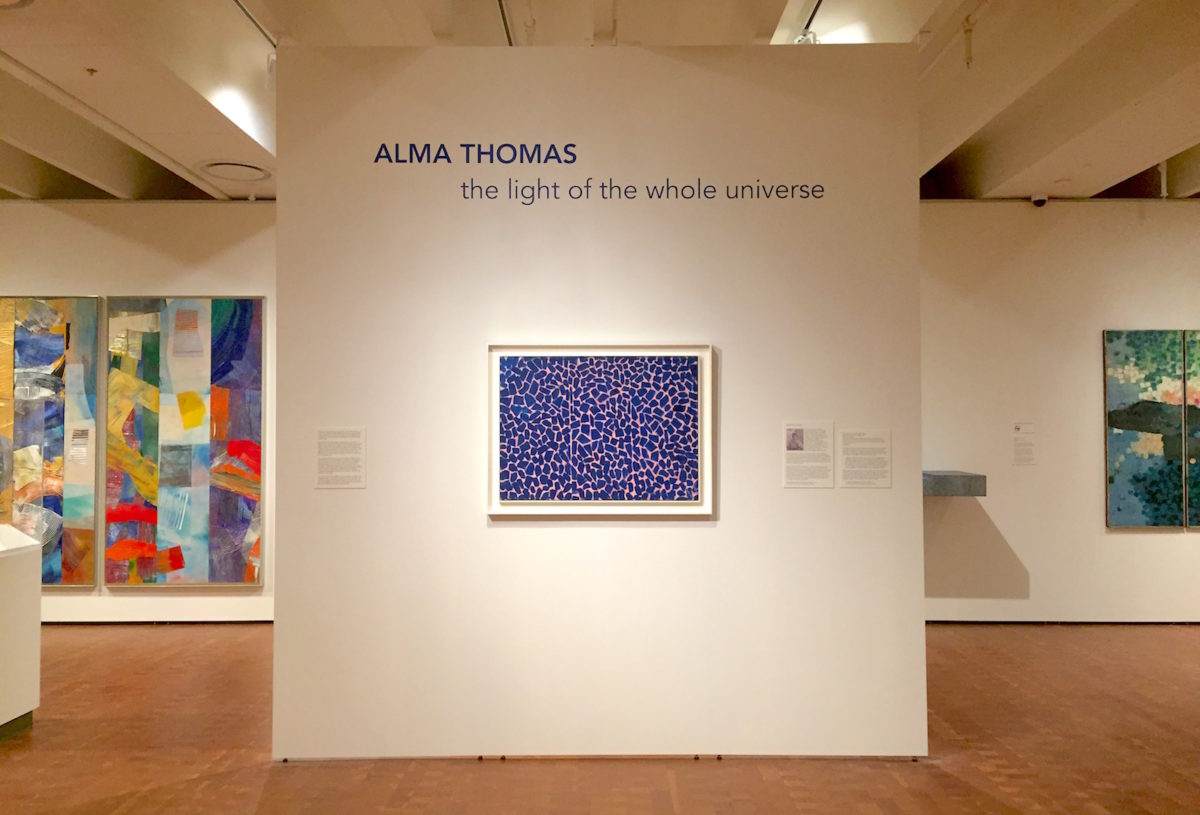

Forty years after her death, DC artist Alma Thomas is becoming a museum idol, one of a hyper-select group of artists around whom institutions are building their permanent collections.

Artwork by the trailblazing African-American expressionist hit a new auction high last year, and the list of prominent institutions acquiring her work in recent months includes Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Arkansas; the Hood Museum of Art at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire; the National Museum of African American History and Culture; the White House Historical Society (for display in the White House); and the Smith College Museum of Art in Massachusetts.

Emma Imbrie Chubb, curator of contemporary art at the Smith College Museum of Art, pushed for the 2018 acquisition of Thomas’ 1973 painting Morning in the Bowl of Night, which has since become a centerpiece of the museum’s redesigned permanent collection.

“A work by Alma Thomas was a priority for Smith for a few reasons. First and foremost, Thomas made a signal contribution to abstraction,” Chubb said.

In 2016, Hood Museum of Art director John Stomberg recommended that museum’s purchase of Thomas’ 1969 painting Wind Dancing with Spring Flowers, which he found exhibited at an art fair in Chicago.

“[The piece] is a total knockout,” Stomberg said. “It is a singular and forceful work of abstraction that embodies the joy of color and harmony in the best of the modernist tradition.”

Former President Barack Obama helped bring appreciation of Alma Thomas’ art to this new level by selecting multiple works by the artist in his first-term redecoration of the White House. The Obamas added a third Thomas, in 2015, at the head of the table in the renovated formal family dining room. Owned by the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Gallery, one of the artworks displayed in the Obama White House is visually similar to the painting acquired by Smith College.

First in her class — and first a teacher

Theater aficionados may know that actor and comedian Robin Williams was the very first graduate of the theater program at Julliard, the famed New York City music academy. Similar fun fact: Alma Thomas was the first graduate of the fine arts department at Howard University.

After graduation in 1924, Thomas was active in the local arts community, including helping to establish a gallery that represented black artists. She also worked as a teacher of visual arts in DC Public Schools (DCPS) for more than than 30 years, retiring in 1960 at the age of 68. It was only after her retirement as a teacher that Thomas began regularly exhibiting, and all of her acknowledged masterworks are from this “late” period.

“Alma Thomas left an indelible mark on countless DC Public Schools students as a teacher at Shaw Junior High School,” interim DC Public Schools Chancellor Amanda Alexander said. “Her legacy lives on today and thanks in part to her dedication to DCPS, arts education remains an integral part of our efforts to ensure joyful and rigorous learning in our schools.”

When she retired from DCPS, Thomas’ reputation as a teacher was firmly secured. In the succeeding years, with newly available time and energy, Thomas re-established her studio practice as an exhibiting artist and, in a most unusual fashion, received overwhelmingly positive response.

“From an outside perspective, Thomas’ ‘mature’ style seems to have appeared out of nowhere, when in fact she worked very hard to get to where she got,” said Jonathan Walz, director of curatorial affairs and curator of American art at The Columbus Museum in Georgia and co-curator of an Alma Thomas retrospective currently in development jointly with the Chrysler Museum of Art in Norfolk, Va. “She deserves all the credit she received and then some. She definitely paid her dues, just in a quieter way than many other artists.”

Acclaim late in her career

Vincent Van Gogh had a tragically brief career, dying at age 37 and having enjoyed no commercial success at all. Johann Sebastian Bach was in his own time a composer of modest reputation, better known as an organist, who made his living as a church music director. Thomas, whose career as a working artist began only after her retirement from teaching, had amazing success — but only very late in life. In 1972, when she was 80 years old, she became the first African-American woman to have a solo show in New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art.

“Once she started making her own work, she was showing fairly quickly at galleries and then had the Whitney show,” visual arts scholar Lauren Haynes said in a 2016 interview with CultureType.

Haynes — now curator of contemporary art at the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art — was co-curator of a highly regarded Alma Thomas exhibition in 2016 that was organized jointly by The Studio Museum in Harlem and the Frances Young Tang Teaching Museum and Art Gallery at Skidmore College in Saratoga Springs, N.Y.

“She was able to see her work in museums while she was alive, which is something that not all black artists who were making work at the same time that she was really were able to do,” Haynes said. “That was this amazing, really I think important, part of her story.”

While some have pondered what Thomas might have achieved had she begun exhibiting at a younger age, Haynes pushed aside such speculation in a recent interview with The DC Line. “It’s hard to comment on how her career would have developed if she had achieved success when she was younger because her work wouldn’t have necessarily been the same,” she said.

In the years since Thomas’ 1972 Whitney solo show, museums and high-end galleries have frequently displayed her works, but the past decade has brought an additional dimension to that attention: an intense effort to research and understand the artist.

In May 2018, responding to public interest, the Smithsonian Institution’s Archives of American Art unveiled a fully digitized Alma Thomas archive, including primary source materials once owned by the artist.

“I think of greatest interest are her autobiographical writings, her exhibition files … and her scrapbooks that document her teaching career at Shaw Junior High School,” said Liza Kirwin, deputy director of the Archives of American Art. “They give an intimate view of her life and work.”

Living in ‘the fast lane’ on 15th Street NW

Charles Thomas Lewis, a federal government employee, has his own intimate understanding of his famous great aunt. After spending parts of two summers living with her — first in 1969 and again in 1970 — Charles and his mother moved from Columbus, Ga., to DC and into Alma Thomas’ house on 15th Street NW the next spring. The pair lived with Thomas on and off for the rest of her life.

“It was like going from the slow lane of traffic into the fast lane, and everyone was speeding,” Lewis said in an interview with The DC Line. “I met people who I would never have met if it was not for her.”

Thomas’ social circle included fellow artists Jacob Kainen, Lois Jones Pierre-Noel, Delilah Pierre and Sam Gilliam. Lewis also recalls meeting Vice President Hubert H. Humphrey with his aunt.

Lewis, who is executor of his great aunt’s estate, supports the efforts by a growing number of institutions to participate in her artistic legacy.

Alma Thomas and her extended family have deep ties to the western Georgia city of Columbus, where work is underway for the retrospective. She was born there in 1891 to John Harris Thomas and Amelia Cantey Thomas, who moved their family to DC in 1907. Alma Thomas had three younger siblings.

The Columbus Museum owns an important tranche of archival materials related to the artist, once property of the artist’s youngest sister. Along with materials from the Archives of American Art and additional public and private collections, the documents held by the Columbus Museum are helping to shape the exhibition that Walz is developing with Seth Feman, curator of exhibitions and photography at the Chrysler Museum of Art.

The co-curators are striving to present a holistic picture of the artist in their exhibit, which will be augmented by a catalog of scholarly essays published jointly by Yale University Press and the Columbus Museum. The traveling exhibition will debut at the Chrysler Museum of Art in the summer of 2021 and then visit two yet-to-be-selected cities before winding up at The Columbus Museum in 2022.

“Over time, Thomas has become mythologized, and there is this persistent triumphalist narrative that makes her seem almost superhuman,” Walz said. “As co-curators, we can confirm her many accomplishments, but we’d like to present her as a fully rounded human being who was incessantly curious, continually growing, and always learning — even from her mistakes and failures.”

Part of a revised, more diverse art history canon

Thomas’ ascendance comes amid broader changes happening in museums today. “It’s critical to acknowledge that the story of modernism and abstraction has, for a long time, been shown in U.S. museums and taught in its classrooms as the sole domain of a few artists, who were mostly male, straight, white and in New York,” Smith College’s Emma Chubb said. “Even though that was never the reality.”

To revise the story told on museum walls, the works on display are changing.

Several months ago, when the Baltimore Museum of Art de-accessioned works by highly regarded white male painters from its permanent collection, gallery officials said they hoped to use the funds to acquire works by a more diverse set of artists, including Thomas.

“Every museum in the country that actively collects art currently strives to rewrite art history in such a way that past transgressions are acknowledged and corrected,” Hood Museum director John Stomberg said. “That inclusiveness now informs our mandate. While Alma Thomas figures in this corrective moment, her work transcends the vicissitudes of history.”

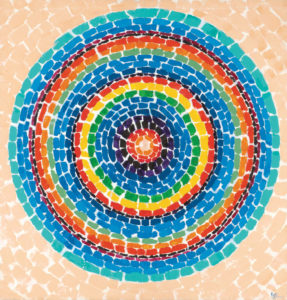

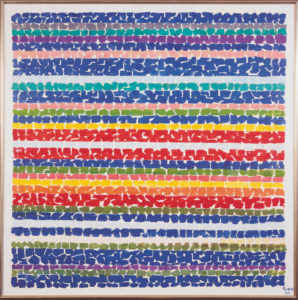

With her place in art history expanding, contemporary descriptions of Thomas’ artwork are increasingly detailed. New York Times visual arts critic Roberta Smith noted, “Her dappled fields, stripes and concentric rings of color bring an energetic bluntness and unencumbered joy to the usual refinements of Color Field and Minimalism.” And New Yorker visual arts critic Peter Schjedladl wrote, “The uncompleted arc of her talent makes her a perennial artist’s artist.”

Recognizing her importance as a local public figure, the DC Public Library is reportedly considering prominent recognition of Alma Thomas within the library system. Asked for comment by The DC Line, library spokesperson George Williams said, “It is too early for us to discuss what shape that might take.”

Meanwhile, an unincorporated but influential group of arts supporters have organized themselves as the Friends of Alma Thomas to support similar efforts.

DC Public Schools, where Thomas spent so many years as a teacher, is also considering honoring her legacy. School officials — currently in the process of selecting a name for a new Ward 4 middle school scheduled to open next fall — are offering “Alma Thomas” as one of 10 potential choices in an online survey open through Oct. 30. The survey’s biographical sketch highlights the art clubs, lectures and student exhibitions that Thomas organized at Shaw Junior High, alongside her many other local ties.

DC is in many ways a small town, so it’s a matter of pride when artists with local ties — whether that’s author and screenwriter George Pelecanos, opera singer Denyce Graves or comedian Dave Chappelle — enjoy success. Now, 40 years after her passing, not just DC but the art world writ large is celebrating the artwork of DC artist Alma Thomas.