After a tree fell, the backyard studio where artist Lou Stovall screen printed his own and others’ artwork for nearly 50 years had to be razed—but his legacy persists.

I wrote this for print in the Washington City Paper and it is online on their site here.

Artwork from Lou Stovall’s print studio, Workshop, Inc., is ubiquitous in local galleries and museums. Pieces populate institutions like the National Gallery of Art and the Smithsonian American Art Museum, as well as the American University Museum, D.C.’s Art Bank, the Phillips Collection, and Addison/Ripley Gallery. But unlike many of the artists he created prints for and with, including Sam Gilliam, Josef Albers, Alexander Calder, Gene Davis, Elizabeth Catlett, Lois Mailou Jones, and Jacob Lawrence, Stovall’s name has yet to seep into the mainstream. And though Stovall has produced his own artwork—mainly silk-screen prints, but also collages and assemblages—along with prints for other artists from his backyard studio for decades, now, due to the artist’s age and an act of nature, his future output is in jeopardy.

During a rainstorm on the evening of May 8, 2020, a large tree fell through the Workshop, Inc. studio, which is located behind Stovall’s Cleveland Park home. Branches penetrated the roof, and the overall weight crushed in the ceiling, leaving the space open to the wind and rain. In addition to the printing stations, the studio housed walls of flat files storing hundreds of artworks by Stovall and the artists he has worked with over the last four decades. The impact was so shattering that the building was razed five months later. His wife Di Bagley Stovall, an artist herself, described the loss as “devastating.”

Stovall, who moved to D.C. in 1962 to study fine arts at Howard University, is a master of silk-screen printing. A 1998 New York Times profile of Stovall quotes Lawrence, one of the most important 20th century creators of narrative artworks, describing Stovall as “a craftsman who is also an artist.”

The volume of Stovall’s output—which includes prints for other artists, his own artwork, and prints made for commercial and community use—is vast and diverse. But, as Lawrence’s description reinforces, evaluations of Stovall have commonly centered on him as a craftsman more than as an artist. In 2001, Paul Richard wrote in the Washington Post that “As a printer of his own art, and of the art of many others, as a framer and installer and shepherd of collections, Stovall has inserted more art into Washington than almost anyone in town.” The Workshop, Inc. space was also a frame shop for fine art for many years, and Stovall was available to install and maintain fine art collections.

Now, Stovall is increasingly getting his artistic due; for example, there’s a current solo show of Stovall’s artwork at the Columbus Museum in Georgia. Harry Cooper, senior curator and head of modern art at the National Gallery of Art, says, “He took color screen-printing, which is often regarded as a more commercial form, to new heights, both in his own work and that for Sam Gilliam.” Cooper also noted Stovall’s “gift for delicate line and bold color, and an elegance that pervades even his most energetic abstractions.”

Born in Athens, Georgia, Stovall earned his Bachelor of Fine Arts from Howard in 1965. Having worked his way through school at a commercial print shop, he was able to set up the Workshop, Inc. studio in 1968 with support from a Stern Family Fund grant that required him to also use the studio to teach printmaking, which he continued to do into his 80s. A multi-year Stern Fund grant was also made to Gilliam, a longtime Stovall collaborator. Gilliam says the grant provided him with the resources to work full-time as an artist.

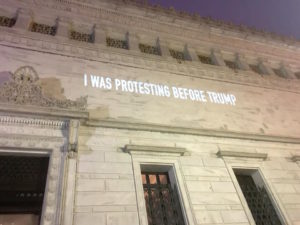

Stovall’s output over the years is varied, including works with text, flowers, landscapes, and abstract color work. “First known for his activist posters, Lou’s art has long embraced elements of nature in parallel with a complex of abstract principles of image-making, with one or the other of these concerns taking priority at different times,” says Ruth Fine, a curator at the National Gallery of Art from 1972 to 2012, who was involved in several acquisitions of Stovall’s work. Stovall’s flowers are reminiscent of fellow D.C. artist and Corcoran benefactor Lowell Nesbitt’s, but tend to have more breathing space around the main subject. Recent color forms easily remind one of similar work by Gilliam.

When evaluating any artist, the knowledgeable viewer commonly finds influences. But critiques of Stovall’s work may have suffered through the years because those influences can be so readily identifiable. Depending on the decade, critics have described his work as “intricate and refined” or evaluated it as “serene abstractions.” Undeniably, his own artwork is compared to his most famous and consistent collaborators—Gilliam and Lawrence—and deeply linked with the craft of silk-screen printmaking.

Silk-screen printing is easy to understand but difficult to master. Stovall’s creations from the 1960s to the present show mastery of the form and experimentation with its limits. The practice of creating fine art silk-screen prints entirely by hand, as Stovall did, has all but disappeared with new, computer-aided production methods. But during the decades of his greatest output, if an artist wanted a hand-inked version of their work that they could sign and sell as original artwork, silk-screen printing was perhaps the best option. Working with his artist colleagues, Stovall would begin either from an existing artwork or fully from scratch to match ink colors brought or described to him, to cut the stencils, and to create the image in layers by squeezing ink through a silk screen, one color at a time. Each color added to a print has to be allowed to dry because the paper, which is laid underneath the stencil and screen, will otherwise smudge the ink. To produce just 50 prints of an artwork including 10 colors requires 500 individual passes, with time to dry between each, and only that few if each pass is completed perfectly. Some pieces Stovall produced required more than 100 colors. Any imperfection, whether it appears on the first or last pass, means the piece is discarded. The painstaking attention to detail required to produce silk-screen artwork at scale is stunning.

Interest in Stovall’s output has increased over the last two decades, along with interest in other African American artists, including Alma Thomas and Gilliam. Aaron Brophy is a sculptor and teacher of visual arts at the nearby Sidwell Friends School who also curates exhibitions for the school’s Rubenstein Gallery, including recent shows of works by Gilliam and Carol Brown Goldberg. In 2018, Brophy curated a two-part solo show of Stovall’s artwork: One section featured works created by Stovall alone; the other showed art in which Stovall was a collaborating printmaker.

“And one of the early pieces was a poster he made for [Dance Theatre of] Harlem,” Brophy says. “And that made me realize, there’s really a kind of throughline in Lou’s work from the Harlem Renaissance and his work with Jacob Lawrence and his connections with Sam Gilliam, all the way through the ’70s, ’80s, and ’90s. Looking across his output, we see Lou has literally been relevant for 50 years, as an artist and also as a collaborator with other artists.”

“Sam Gilliam’s very first international retrospective wasn’t until two years ago,” Brophy continues. “It’s interesting to watch this resurgence of artists from the ’60s and ’70s … to see curators and museums picking up this thread and finally recognizing artists like Lou, like Sam.”

In 1968, Stovall took over the lease of a closing gallery to start the Workshop, Inc. business. In that Dupont Circle space, he created commercial prints, taught, made frames, worked on his own art, and helped others make their own silk-screen artworks. Lou and Di Stovall married in 1971; in 1972, they moved to the Cleveland Park home where they still live and brought the business with them. Eventually, they set up the print shop in a detached garage in the back, and over time the space was modified and expanded to better meet the needs of the business.

Three categories of visitors have consistently trafficked Workshop, Inc.: collectors, artists, and students. And while Stovall built an American art institution, one ink layer and one print at a time, he and Di raised their son Will in a creative and community-minded Cleveland Park that has slowly changed around them.

Even as Workshop, Inc. rose to prominence within the national art scene, Stovall remained an active participant in the D.C. and Cleveland Park communities. In addition to serving as a commissioner for the DC Commission on the Arts and Humanities, he regularly made prints for community organizations, concerts, and benefits. Judy Hubbard, a Cleveland Park Historical Society tour guide, longtime community activist, and retired director of constituent services for Ward 3 councilmember Mary Cheh, describes an early 1970s Cleveland Park community campaign asking drivers to slow down on Reno Road near John Eaton Elementary School on Lowell Street NW; Stovall created the campaign poster. And when collector Susan Talley, a longtime Cleveland Park neighbor, decided to see if there might be interest in starting the now-influential unincorporated Friends of Alma Thomas group, “the first person I went to visit, called and went to visit, was Lou and Di,” she says. “And they were very supportive.” The pair helped connect Talley to David Driskell and the Driskell Center for the Study of the Visual Arts and Culture of African Americans and the African Diaspora at the University of Maryland and to other collectors of Thomas’s artwork.

The creative back-and-forth among neighbors was once one of the draws of moving to Cleveland Park, a neighborhood that has a long history of artistic and intellectually engaged residents. One of the Stovalls’ notable Cleveland Park neighbors was photographer and sculptor William Christenberry. And, like Stovall, Christenberry made his artwork in a studio attached to the family home—in his case, not an expanded detached garage, but an addition. “It was a very interesting, vibrant neighborhood,” his wife Sandy Christenberry says.

Hubbard, the community activist, started her career as personal secretary for Helen “Leni” Stern, the influential artist and philanthropist. A Cleveland Park resident since the early 1970s, Hubbard says the neighborhood has always included authors, activists, intellectuals, and visual artists, mentioning David Ignatius, Christopher Buckley, Susan Shreve, Milton and Judith Viorst, Peter Edelman and Marian Wright Edelman, and Dickson Carroll. “This is a very intellectual activist neighborhood,” Hubbard says. Still, as the city as a whole has gentrified, the neighborhood has become less economically diverse, and it’s hard to imagine working artists being able to move into the community today. According to U.S. census data, median income for a Ward 3 household has risen from $45,000 in 1990, to more than $126,000 in the most recent data.

Stovall’s commitment to teaching neighborhood children, including students from Sidwell Friends School and fine art students from area colleges, models how an artist can be a positive influence on a community. Poet E. Ethelbert Miller, Stovall’s longtime friend and colleague, says “I’ve always felt that Lou having a workshop behind the house was very special, especially for young people … I always felt that this is the type of artist I aspire to.”

Andrew Christenberry, the son of William Christenberry and a sculptor and furniture-maker in his own right, grew up aware of his influential neighbor’s work. “Lou is an absolute master printmaker, and he was quite known for that,” he says. “If you’re a painter or draw and you want to work in the print medium, you often need help because it’s very technical.”

It’s not uncommon to think of artists of Stovall’s caliber as bold and full of ego, but his neighbors describe him as anything but that. Susan Talley says Stovall “sort of subverted his own ego in some ways to other artists … They were the stars, and his skill is immense in what he was able to help them accomplish.” And Anthony Gittens, a longtime friend and colleague who worked with Stovall when Gittens was executive director of the DC Commission on the Arts and Humanities, remarked, “You go into Lou’s studio and his art is there, but you also see so many other excellent artworks. Lou talks about other people’s work as much as he does about his own.” In the 1998 New York Times profile, Stovall himself is quoted saying, “The most important part of what I do is to give artists who have ideas they want to express in a silk-screen a way of doing it.”

Walking through the wreckage of the space with Di Stovall before it was demolished, she recalled hurriedly removing art from the studio after the tree’s fall in the tones of someone recounting saving a child from the path of a landslide. She also confirmed that the Workshop, Inc. studio will be rebuilt, but it’s unclear where Lou’s future artistic process will take him. Now that he is 84 years old, the work of cataloguing, displaying, and preserving artwork may become a bigger part of what’s accomplished in a future space.

Sorting through nearly half a century of artistic output is no easy feat. Since William Christenberry died in 2016, his wife Sandy has slowly confronted reconfiguring the space in their home that includes her late husband’s work. For now, his studio space is less of a work space and more a storage unit. “You know, it’s been four years since Bill passed away,” she says, “and I’m still trying to figure out what to do … Because I want to have people come to visit the studio again.”

In November 2020, Stovall’s damaged studio was razed. Decades of brilliant output currently have no permanent home. As Stovall’s work is sent out for upcoming exhibitions and becomes a part of the narrative of art history, the studio’s destruction is likely to remain a marker—though not an end point—in an artist’s exceptional career.